Jarre-ing experiences

As a child in the early 80s I was aware of synthesized sound. I don’t know why I found the bloops interesting - perhaps it was the frequent presence of “synthetic electronic sound” in science fiction TV shows that resonated with me. Or maybe it was because these sounds weren’t ordinary and everyday.

Though I was aware of the early 80s synth pop boom to some degree (I certainly remember when Don’t You Want Me (1981) and Blue Monday (1983) came out), I was more focused on electronic musical cues from Doctor Who, or the laser sounds from Star Wars and Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, or Vangelis’ ubiquitous 1981 synth hit Chariots of Fire. (I remember being especially impressed by how Vangelis’ studio setup had him besieged by keyboards.)

My most vivid experience of this sound was when - more than once - our local TV transmitter would sometimes lose its feed and we’d be shown a test pattern accompanied by strange electronic music. I don’t know why but I found this music weirdly compelling.

At some point the weird music got replaced, or maybe the Transmitter feed became more reliable, and this phenomenon was left behind in the early 80s. I continued to notice electronic music though, as the 80s rumbled on:

- the Art of Noise’s Close to the Edit (1984)

- Paul Hardcastle’s Nineteen (1985)

- MARRS’ Pump up the Volume (1987) was also a revelation (though I think I was possibly more elated by the royalty free Nasa footage used in the video than its pioneering house-in-the-charts sound).

I don’t want to over-emphasise these memories - children are fleetingly interested in lots of things, and perhaps without later connections I wouldn’t have ended up taking the interest any further.

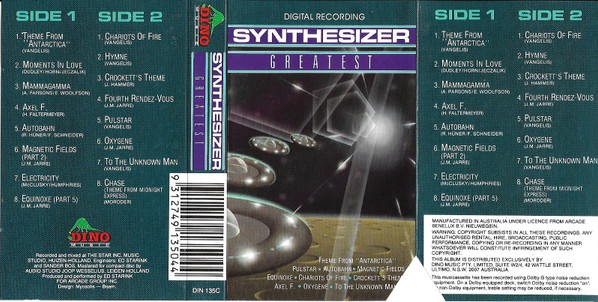

Then, in 1990, I saw a cheesy ad on TV for Synthesiser Greatest (volume 1), a collection of synth hits distributed in my homeland by the cheap and cheerful Dino Records. The ad featured a tune I recognised from the TV transmitter breakdowns. At this point I was 14, and had never bought music before, but I was sufficiently moved to buy this compilation. And so it was, on my 15th birthday, I acquired Synthesizer Greatest on cassette.

The album, as I discovered later, featured covers only (boo!) by a Dutchman going by the name Ed Starink. (I thought this name was an embarrassing pseudonym, but as best I can tell it isn’t…?) It’s not the sort of record a conoisseur would be proud to have in their collection, but as a starting point for further research it was actually very valuable. Here’s a list of some of the tracks:

- Autobahn (Kraftwerk)

- Moments in Love (Art of Noise)

- Electricity (OMD)

- Pulstar (Vangelis)

- Oxygene part IV (Jarre)

- Crockett’s Theme (Hammer)

Truly, a glittering collection.

Let’s give it up for Synthesizer Greatest. clap clap clap

The track I recognised from the test pattern accompaniment was called Oxygene part IV, and composed by a fellow namedJean Michel Jarre. I wanted to hear more, and over the next couple of years I obtained (new, second hand, or cough dubbed onto tape) around ten Jarre albums. The rest of this post is devoted to reporting what I found.

Brief side note

But first: a bit of insecurity. As best I can tell from friends who are music snobs, my entry into music collecting is quite idiosyncratic. Kids tend to start buying music much younger than I did, and good collectors are electic. By contrast, when I did start, late, my interests were pretty narrow, and even as an adult I’ve never been eclectic. I tend to like very little of what I hear. To give you a sense of my depravity (at least, my depravity compared to fellow late Gen Xers):

- the only Nick Cave I’ve heard is a greatest hits CD (I liked it well enough)

- I’ve never enjoyed any Pixies songs, save for the one about the monkey

- every time I’ve tried to listen to Sonic Youth I’ve quickly gotten bored and turned it off.

In my head there’s an alternative universe where I did it “right”, picking up fresh white label house 12” records rather than listening to a naff Frenchman. But that’s not this universe and here I am, writing a blog post about what I think of him, for my son to stumble over after I’ve snuffed it.

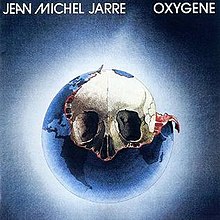

Oxygene (1976)

Oxygene wasn’t the first Jarre album I heard, but it makes more sense to start here.

Autobiography

So, it’s the middle of 1991 and I want to buy this LP. It’s reasonably easy to find it in record shops, and I have two choices: obtain it on cassette tape for $19.95, or on CD for around $33, $34. Or, I can play it “safe” and buy a classical music (this was my other musical interest at the time) cassette for as low as $10 (synth music wasn’t the only thing I was into at the time). My financial resources at the time were feeble (aye, but it taught me the value of money) so I was in a quite a quandry. Eventually curiosity got the better of me, and I resolved that I will take my chances and buy Oxygene.

I still get misty eyed remembering that fateful day in August 1991. It was a sunny Wednesday and I caught the lunch time train from school into town for an orthodontist appointment. Afterwards, rather than return immediately to the train station as was expected of me, I ducked out to the nearest music shop (of which there were many back then). With my braces tightened, and teeth hurting, I executed my musical purchase and sprinted to the station in time (just) to catch the next train back to school. Safely onboard, I placed the tape into my budget Philips personal cassette player (no Dolby B noise reduction, but it did have a three band equaliser, and I loved it). I pressed play and listened through the first side. I remember being feeling a sense of mystical entrancement and relief the purchase was worth it. Unfortunately school got in the way of listening all the way through there and then. When I got home, though, side two proved to be as captivating as side 1. That day, for better or worse, I became a fan of Jarre for life.

Album

Oxygene part 1 starts with a genial cyclical burble of synth through echoes and phaser. Eventually the bubbling subsides into a subdued, eerie thereminesque theme. Then initial burble returns to facilitate the transition into Part II. Overall part I is a fairly straightforward mood piece, but it sets the scene well.

Part II commences with a repeating, urgent sequencer line that builds to a crescendo before yielding to a dramatic melody, punctuated by echoed sine wobbles from a VCS3. (I was delighted to hear this track as it’s another tune I remember from TV transmitter breakdown interludes.) After the first melody, the track shifts into another theme, which thunders away emphatically with a bit of noodly soloing, until the track fades away into a slow up-and-down sweep of white noise through a Small Stone phaser, perhaps the most iconic effect on Jarre’s first two albums.

Part III is a more sedate, oriental-sounding piece, which ends with a field recording of birdsong. Not much to say other than I like it. This brings side 1 to a serene conclusion.

Oxygene part IV I already knew from Synthesizer Greatest. I learned a lot later though that when creating the track Jarre just slowed down Hot Butter’s Popcorn, and slopped on a bit more grandeur. It’s a preposterous scenario, but it works. (Now I think about it, Darude’s Sandstorm isn’t far off Popcorn either.)

Oxygene V starts with what a slow hymnish refrain. The chords are slightly ponderous, but before they get stale they get replaced with the same notes sped up, with a bit of moog brassy soloing in a mode reminiscent of Ravel’s Bolero. (This slow then fast structure is suspiciously reminiscent of Kometenmelodie I and II from Kraftwerk’s Autobahn album which came out a couple of years earlier. Concidence?!?)

The album’s finale is part VI, a track whose arrangement screams “cheesy French lounge music, on a beach, with synth seagulls”. Despite this, and perhaps because it’s in a minor key, the track is successful in providing an ambiguous conclusion to the album, and it’s a good choice.

Waxing lyrical

From the beginning, the sound world of Oxygene has always been for me a crepuscular world of stone, sky, wood, and water, devoid of people. It’s the sound of the planet before humans evolved, or the planet that will exist after we’re gone. To continue the pseudo-poetic vein, it’s the sound you might hear if you could only strip away the overlying noise of human fuss.

But to be more concrete, I think there are two primary sources of genius for Oxygene: the sound and the album’s track sequencing.

The sound feels very crisp, precise, and clear - despite being recorded in Jarre’s kitchen rather than in a proper studio. That the album was constructed with only 8 tracks is mind-boggling. The elements seem perfectly balanced against each other in terms of stereo space, relative volume, and audio frequency.

In terms of sequencing, the tracks work well to enhance each other:

- Part I introduces the sound world

- Part II adds some drama

- Part III relaxes the mood and adds additional contrast

- Part IV restarts proceedings and functions as the heart of the album

- Part V begins as a languid change of pace, before stepping up a gear and providing a bit of arcadian longing

- Part VI provides a muted “come-down” to conclude the album.

This sequence of tracks provides a good variety of contrasting moods. Balancing these contrasts, the album’s continuous mix (aside from the gap between side 1 and 2) adds a sense of continuity: listing to Oxygene feels like a journey.

Now I’ll concede that a 16 year old first time listener today might not have such a vivid listening experience as I did. And at the time of its release there were plenty of critics who felt Jarre’s concoction was slight, facile, cold, and emotionless. I can see how people might feel that way. For my money ($19.95 in 1991 NZD) though, I reckon that Oxygene is the most quintessential document of 70s electronica. There are other albums I think are more important and influential, but if you had to pick one that best utilises the range and techniques of 70s analogue hardware, Oxygene is my pick.

Finally, let’s praise Jarre’s winning choice of Michel Granger’s forbidding, surreal painting as the album’s cover.

Jarre’s prehistory

Before we go further, it’s worth dicussing Jarre’s origins. Well, he was born in France in 1948, and spent his youth being the estranged but well-funded son of oscar-winning film composer Maurice Jarre. In the late 60s he studied electronic music under musique concrete pioneer Pierre Schaffer at IRCAM in Paris. In the early 70s he moved from the academic world to the more prosaic world of advertising jingles, accumulating gear. In 1973 he released two albums. One was a set of stock music, the other a film soundtrack.

I didn’t get to hear these albums until the 2010s. I can report they’re pretty average - standard electronic fare for the time, and only worth listening to once. Sort of “novelty” bleep bloop stuff. These rather unpromising albums make Jarre’s success with Oxygene even more surprising. Just what changed in Jarre’s outlook between Les Granges Brûlées in 1973, and Oxygene three years later? My guess is the difference in quality can be explained by a mix of improved ability, serendipity, and lot more effort put in than compared to those previous albums.

Embarrassing music video

Jarre’s videography is pretty eyewatering, and I’ve chosen to document it here, for shits and giggles. So without further ado, here’s his debut!

He began as he meant to go on…

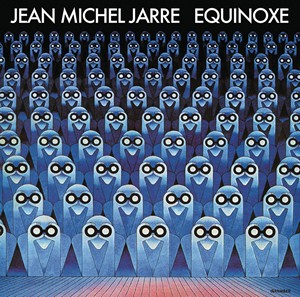

Equinoxe (1978)

Since Oxygene had proven an excellent purchase, I quickly resolved to buy Jarre’s followup, 1978’s Equinoxe. I obtained it the afternoon before I went up country on a three day school trip with my history class. While the coach’s loudspeakers blared out Bob Marley, I cranked up my Walkman and experienced Equinoxe for the first time. (Incidentally I’ve held a grudge against Marley fans and boycotted his music ever since - even though it’s hardly his fault.)

Equinoxe Part I is a major key fanfare realised through frenzied arpeggiation. It is a more confident, emphatic, even bombastic start to its album than Oxygene’s part I. Part II, a haunted, phased soundscape, is much more restrained. Part III kicks off as a delicate waltz, which soon decays into a some sonic brooding and bubbling, before Part IV kicks off with much sturm and drang. This track was the album’s most exciting discovery for me: in the early 80s in my country it has been used as the title music for a long-running nature documentary series in my country. It turned out Jarre had played a bigger part in my life than I’d hitherto thought.

Side two begins with Part V, which I’d heard before on Synthesizer Greatest. It’s very much the album’s single: jaunty, cheerful, pointing the way towards our Glorious Utopian Future. It’s decent enough, but doesn’t have the mystery of Oxygene IV, though.

Part VI is a continuation of Part V’s tempo, and rhythm, is charming in a burbly, techno futuristic sort of way. I like it more than part V. I don’t have more to add except to say: it’s jolly.

Part VII starts off by pulling back to a nice sequenced synth bass solo. (Now’s as good a time as any to mention that on Equinoxe Jarre collborated with engineer Michel Geiss, who built a custom digital sequencer for the project. As a result Equinoxe is definitely more rhythmically propulsive than Oxygene.) The piece develops into a lengthy and slightly underdeveloped workout that doesn’t quite justify its length. Eventually the rhythm, which hasn’t relented since Part V began, eases away. Part VIII starts out with synthetic rendering of an “oompah” band playing in a thunderstorm - quirky choice, that - before recapitulating Part V’s theme in a churchy kind of way. The album concludes with a kind of heavenly Amen.

Up to part VII Equinoxe matched Oxygene in terms of quality; the only detracting point being that the album cleaves very closely to Oxygene’s template, and so isn’t as original. (That doesn’t particularly bother me; not every album has to be a significant development on the last.) Unfortunately, however, parts VII and VIII don’t quite see the album out with the same tight focus. In fact the album rather meanders to its conclusion. It’s not enough to derail the whole work, but it is a shame Jarre ran out of inspiration on the home strait.

As for my school trip, Equinoxe was the highlight - well, that and getting a chance to have a chat with a girl I fancied. To be fair the opportunity was wonderful, but I fear I squandered it by boasting about how much weetbix I could eat. Shame bro!

Embarrassing music video

Oof. But credit where credit’s due, he’s wearing a hell of a cravat.

Magnetic Fields (1981)

Magnetic Fields found Jarre at something of a crossroads. With Equinoxe being a play-it-safe sequel to Oxygene, 1981 found the Jarre sound unchanged from 1976, while there had been rapid technological development opening up new styles of music. To avoid looking like yesterday’s man, for his “third” album (ignore everything pre-Oxygene), Jarre had to evolve too. He made a good choice in obtaining a Fairlight CMI, a fabulously expensive and very much way-of-the-future digital sampler.

The first side of Magnetic Fields is taken up by Magnetic Fields part I. In truth Part I is actually three tracks: an initial urgent introduction that gives an impression of restless motion, followed by an interlude of floating musique concrete, followed by another minor key gallop to the side’s conclusion. Although by no means bad, Part I is nowhere near as scintillating as the first sides of Oxygene and Equinoxe.

Side two begins, as usual, with a single, the rambunctious Magnetic Fields part II. The track is the first Jarre number to feature percussion up loud in the mix, perhaps to appeal to the yoof. It’s not a bad track, but it lacks the transcendance of Oxygene IV, or the goofy charm of Equinoxe part V. Worryingly - for Jarre’s sake - the version on Synthesizer Greatest is a better arrangement than the original (shoutout to my man Ed Starink).

For me the best track on the album is Magnetic Fields part III. It’s a relatively straightforward mix of spiralling arpeggios, water sploshing, slick synth bass and what could be a slowed thumb piano loop. It’s a change of place and looks ahead, just a little bit, to Zoolook.

Part IV is a sort of limp anthem that plods away for a while, modulates into minor key for a further while, and kind of slinks away with a field recording of a train. A bit like Equinoxe part VII it’s not bad, but just not that interesting.

If Part IV is lacklustre, Part V (named on a later Jarre compilation as “The Last Rumba”) is, like Oxygene Part VI, a lounge music excursion. But while its predecessor has a contemplative, even melancholic tone, The Last Rumba is profoundly cheesy, and doesn’t bear repeated listening.

How successful was Magnetic Fields in evolving the Jarre style? Well, he certainly tried, but he ended up stuck between the old and the new. A lot of the familiar synths (VCS3, Arp 2600) are still present, which isn’t necessarily bad, if they’re used in new ways; but unfortunately they weren’t, really. The Fairlight only recognisably appears on two tracks, and isn’t greatly utilised. Another new element, the more complex, layered sequences, actually work to the album’s detriment, creating a wall of sound that muddies Jarre’s previously pristine production clarity. Just to be cruel, compare Magnetic Fields with another album released in 1981: Kraftwerk’s Computerworld. On Computerworld Kraftwerk effectively performed a victory lap by inventing techno (it was their last great achievement, but at least it was a great achievement). Magnetic Fields, however, proved to be a stylistic dead end.

Embarrassing music video

Embarrassing, yes, but an improvement on before.

Zoolook (1984)

Zoolook was the first Jarre album I listened to, obtaining it on CD from my local library in early 1991. It’s perhaps not the most appropriate introduction to Jarre’s music, but in a way that makes it a more interesting starting point. Although on first listen it was very apparent to me “this ain’t no Oxygene IV!”, I was immediately captivated by the album.

Making Zoolook, Jarre had another crack reinventing his sound, and even collaborating with muscians outside his circle for the first time (with collaborators as unexpected as Laurie Anderson and Adrian Belew). The Fairlight CMI, used somewhat timidly on Magnetic Fields, was front and centre on Zoolook. (Apparently the first version of the Fairlight didn’t have a sequencer, and this may account for its limited use on the earlier album.) Also in contrast to earlier albums, the primary musical medium of Zoolook is the human voice, sampled and processed.

The first track, Ethnicolor, is a psychedelic, Vangelistic (Vangelisian?) excursion quite unlike anything Jarre had produced before. The clarity of arrangement makes a welcome return, the digital sampling and recording technology used on the album providing a crisper frequency response than Magnetic Fields’ wall of low-pass-filtered arpeggiating synths. The sound palette is further expanded with live drums passed through gated reverb in classic mid-80s style. Slap bass even makes an appearance, and surprisingly it actually works. The only downside to the track is that the early melody is played through a vocal sample that sounds like “tit”, an embarrassing and obvious gaffe which schoolboy me found hard to take. 30 years later: shrug.

The next track, Diva, features Laurie Anderson on vocals, and begins with a languorous introduction, followed by a more frenetic workout propped up by african-style drumming and guitar. Anderson’s voice outputs glossallalia that is by turns seductive and manic. The result is, once again, excellent.

There follows the title track, a piece of excellent synth funk(!), to my ears reminiscent (but legally distinct, you understand) of Herbie Hancock’s Rockit (cough even down to the music video).

Then there’s the atmospheric Dreamtime evocation of Woolloomooloo. I actually think it’s one of Jarre’s best tracks. Just really well realised.

After that comes Zoolookologie, a fizzing pop track which zings away happily, its only blemish being a recapitulation of that distracting “tit” sample.

Heading into the home straight, there’s Blah Blah Cafe, a stomping piece of silliness that has a similar function to The Last Rumba on Magnetic Fields, only it isn’t fucking terrible.

The final track is the grave, contemplative Ethnicolor II, which is the perfect sendoff for the album.

Zoolook is - to me at least - Jarre’s second best album after Oxygene. What I admire most about it is after the relative failure of Magnetic Fields, Jarre managed to reinvent himself. It was a bold gamble, but to my mind it completely paid off.

Influences?

Because Jarre studied at IRCAM, I’d always assumed that Zoolook was the result of him picking up that thread of his life again. But recently I had a listen through Talking Heads’ catalogue, and it suddenly occurred to me that perhaps another influence is David Byrne and Brian Eno’s 1981 album My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. This splendidly innovative album is a blend of african rhythms, funk, found-sound recordings of human voices. Sound familiar?

The materials might be similar, but the styles of the two albums are quite different. My Life in the Book of Ghosts is skin-of-teeth experimental, a bewildering, kaleidoscopic maelstrom of sound. Zoolook is much cleaner - frosty almost - and much more mannered. But if you were looking for an explanation for Jarre’s change of direction between Magnetic Fields and Zoolook, it’s plausibly My Life in the Bush of Ghosts-shaped.

(I should say that Jarre is allowed to be influenced by anything he likes, and there’s absolutely nothing in Zoolook that plagiarises My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. And it’s also possible Jarre hadn’t heard the album, or that there were other, more direct influences on Zoolook. None of that’s going to stop me idly speculating, though.)

Embarrassing music videos

This is actually not too bad, so as a bonus, here’s one that’s much worse:

DID YOU KNOW THIS WAS MADE IN THE 1980s?

Rendez-Vous (1986)

With Zoolook marking a much-needed fresh start to Jarre’s career, his next album capitalised on this by creating a remarkable fusion of jazz and ambient electronica which both looked back to Miles Davis’ In a Silent Way, and forward to the 90s ambient movement.

Well, that’s the album I’d like for him to have made. But he didn’t. In fact, what happened next (repeatedly, for 10 years!) was pretty dire.

Houston calling

Rendez-Vous has a bit of a backstory you need to understand before we can discuss it, so settle in! It all started when Jarre was invited to perform in Houston for a celebration of 25 years of Nasa and 150 years of Texas. In its final form, the performance was to be played in front of a massive audience, with a light show beamed across skyscrapers in the centre of Houston.

This scenario might seem a bit random for Jarre, but that’s because I’ve neglected to mention Jarre’s concert exploits. His first concert occurred on Bastille Day 1979, when he performed in Paris to an audience of 1 million. At the time this was a world record attendance numbers for a concert. Solid start… Then in 1981 Jarre gave a series of concerts in China, notable for being the first western performances in China since the Cultural Revolution. These experiences made Jarre more than credible as a booking option for the Houston concert. Perhaps Houston natives ZZ Top would have been more appropriate, but for whatever reason, Jarre ended up with the gig.

For the concert, called Rendez-Vous Houston, Jarre went all-in, producing a new album (also called Rendez-Vous) specially for the event. He also worked with astronaut and saxonphonist Ron McNair to prepare a piece McNair would record while in orbit on the space shuttle. Tragically, McNair died in the Challenger disaster in January 1986. A desolate Jarre wanted to pull the plug on the project, but was persuaded to continue. As if that wasn’t enough trouble, the concert perparation and performance was plagued with problems. In the end though the concert was deemed a success, and Jarre was able to advance his concert attendance record from 1 to 1.3 million people.

A massive digression regarding authenticity in Jarre’s live performances

When I turned 17 I shelled out for a VHS tape of Jarre’s Houston performance (I think it was about $40 - oh the extravagance!). Now it may be a function of the video edit but what Jarre appeared to be doing on stage had no correlation with the music, and it left me wondering if he was merely pretending. To be fair, the vid does suggest Jarre’s semi-circular keyboard controlled the lighting in some way, but the fact it was shaped like a keyboard with keys kind of implied it made sound. Most notanly, when Jarre was supposedly playing a “laser harp” - a rig which allows notes to be triggered by interrupting a laser beam - his “performance” didn’t quite match the notes.

It’s not just me seeing these things. The normally genial UK comedian Bill Bailey was moved to declare that Jean Michel Jarre “is a fraud”. So is he? Well, as I hope to show, the truth is complicated…

For starters it’s difficult to replicate a multitrack recording live, esp with the limitations of 70s and 80s synth hardware. There’s one strategy that could work: create a new mix from the original multitrack including some tracks but omitting others, and have musicians perform those parts. A good example of this is Depeche Mode’s 101 concert, (Fletch’s uncertain contributions not withstanding.) From the Rendez-vous concert it seems some performers were present, though it’s not clear whether they were contributing to the audio mix, or were just there for show. Finding the VHS a bit suspect because of its editing, I went to the trouble of listening to the FM simulcast of the Houston concert, and found that much of what is broadcast is tracks lifted verbatim from Jarre’s back catalogue. The most charitable interpretation one can make from this is that Jarre focused on performing the Rendez-Vous tracks and faked it his back catalogue.

OK, so this evidence is fairly damning with regards to “fraud”, but there’s more than one way to evaluate the evidence. Consider, for example, the practicality of organising a performance with all the instrumentation needed to replicate Jarre’s discography with live performers. It’s one thing for the Stones to jangle away with their more straightforward instruments, another to assemble an orchestra of synths and their operators. Jarre’s 1981 concerts in China provide a good case in point. Much more effort was made to perform the tracks live (or at least with different arrangements of their studio versions), and the sound is much less fleshed out, and that’s even with the overdubs Jarre felt compelled to add for the concert album. It’s possible that Jarre decided not to repeat this with Rendez-Vous Houston.

There are other factors. Unlike the Concerts in China, Rendez-Vous Houston was a one off performance, so there was less incentive to be live for a single concert than there would be for a multi-date tour. Also Jarre may also have simply not had the time or budget to organise a genuinely live performance. Or, contention with organising the light show may have lead to greater focus on that over live sound. And indeed, the reality of the Houston concert is that it was primarily about spectable, and sound was very much secondary to the light show. It’s not clear how many of the 1.3 million actually heard the music, given that light travels further than sound. The music might have been important component of the “artistry”, but for an average spectator, how the sound got generated (and especially who composed it) was probably of little or no interest. In other words, the concert could be successful regardless of the origin of its sound.

I’ve spent a lot words examining all this not to exonerate a hero, but because I’ve performed sets of electronic music a few times myself, and, not being able to “perform” very much of it at all, I’ve been left sitting behind a laptop on a stage feeling pretty fraudulent myself. That said, I never showboated wildly on stage the way Jarre did for Rendezvous Houston (though I can’t say that wouldn’t have improved the experience…). In any event, 17-year-old-me’s umbrage (and embarrassment, frankly) remains justified, even if middle aged me’s conclusion is more of a shrug.

There is a hapy coda to the saga of Jarre and live performance: in the early 2000s he released Oxygene: Live in Your Living Room, a performance of Oxygene with the entire original arrangement recreated with multiple performers and synths sufficient to get the job done. From what I’ve seen of it, this performance seems entirely legit, and genuinely impressive. I don’t know if Jarre intended the project as a rebuttal to earlier suspicion and criticism, and if it was, I’m not sure it’s entirely redemptive. All the same it’s good that he did it.

Rendezvous with Rendez-Vous

Finally we come to Rendez-Vous the album. It’s a slight nod to the past (coming ten years after the release of Oxygene, it uses a new Michel Grainger painting on its cover, and features 6 parts like Oxygene does), but unlike the later Oxygene 7-13 album, the music and tone is unrelated to Oxygene (or indeed to Zoolook). Rendez-Vous’ technological innovation seems to be about getting to grips with mid-80s digital synths, and the MIDI sequencing thereof. To my mind eschewing sampler technology was a mistake: while innovative at the time, that generation of synthesizers have a brittle sound that hasn’t aged well, and the airless arrangement compares poorly to the spaciousness of Zoolook and Oxygene. Worse still, in the early part of the album Jarre seems to be wanting to convey grandeur, drama, even bombast, and the result feels as convincing as a Mahler symphony performed by an orchestra of DX7s.

But the album’s most egregious horror is the saccharine single Fourth Rendez-Vous. I first heard this track on Synthesizer Greatest and even 15 year old me thought it a bit trite. The real version does not sound any better.

The only track on the album that I find reasonably decent is the closer, Final Rendez-Vous. This is the track that was to feature Ron McNair’s saxophone. In his honour the track is subtitled Ron’s Theme. It’s an effective piece, if more lachrymose than I’d prefer; it’s difficult to tell whether this was the arrangement as orginally intended before McNair’s death, or if, in light of events, Jarre amped up the misery.

How did Rendez-vous turn out so bad, and why did Jarre turn his back on the creatively rich sound world of Zoolook? I suspect that with synth technology evolving rapidly in the mid 80s, Jarre could have reasonably believed he was creating a sound that had legs, rather than one that would feel crummy and dated in just a few years. We can also speculate about other, less technological aspects at play: perhaps Zoolook had been costly to produce, and/or wasn’t as commercially successful as previous albums, forcing a stylistic change that put populism over experimentalism. Perhaps Jarre was simply pushed for time to produce both the album and Houston concert, and corners were cut with production. In any event, the album sold 3 million copies and Rendez-Vous became the template Jarre’s next three albums.

Embarrassing music video

So bad.

Revolutions (1988)

Revolutions is something of a retread of Rendez-Vous. The concept this time is social, political, and technological revolutions. This is a decent premise with lots of ideas to explore, and the album certainly tries to cover a lot of ground. The production is much more developed this time, with arguably the best percussion patterns (and sounds) of Jarre’s career.

So that’s all good. But the execution is still heavy with bombast and bathos, and, repeating the winning Rendez-Vous formula, Jarre tied the album to another concert (the comparatively under-attended Destination Docklands performance).

Revolutions is not great, but there is one unreservedly decent track: the uneasy and saxy Tokyo Kid. In keeping with the Japanese theme, I think this piece would be quite at home on the soundtrack of a dystopian anime like Akira or Ghost in the Shell - high praise, perhaps, but I think it’s justified.

But the rest of the album… oh boy. The absolute nadir is September, a tribute to an ANC activist assassinated in Paris in 1988. The tribute idea is of course perfectly decent, but the tune is so sugary (and features a children’s choir, ffs) it’s impossible to take.

Embarrassing music video

Ugh.

Waiting for Cousteau (1990)

A tribute to scuba-diving mariner Jacques Cousteau, side one features something no one asked for: Jarre’s take on calypso music (quelle horreur!). Side 2 features the long, ambient title track, which is pretty decent, if derivative of Brian Eno’s dreary Thursday Afternoon-style ambience. The overall effect is “meh” more than anything else.

Not embarrassing music video

Music’s not great, but give it up for the animators!

Chronologie (1993)

Chronologie (a concept album about Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of time, apparently) is an improvement on Waiting for Cousteau, but nowhere near Jarre’s best. In fact there’s a general sense of watertreading with this album, a feeling reinforced by the odd half-hearted nods to contemporary electronic dance.

I have fonder feelings towards this album than perhaps I should, because I bought it in Australia on my first visit there, and hearing it reminds me of a happy holiday.

Embarassing music video

More boring than embarrassing, really, save for the moment where Jarre spins around to face the camera in a manner reminiscent of Garth Marenghi.

Oxygene 7-13 (1997)

I consumed all of Jarre’s extant albums in 1991, and still had enough interest to check out Chronologie in 1993. Jarre didn’t release any new material for four years and I largely moved on, discovering other (better? certainly less dubious) electronic practitioners. But when I discovered Oxygene 7-13 in a record shop in the winter of 1997, this new disc induced sufficient intrigue that I bought it.

Brought out for the 20th anniversary of Oxygene, the new instalment was a return to that sound world, with Jarre utilising (mostly) the same synthesizers.

The first track (part VII, continuing on from the six parts of the original album), is an absolute tour de force, one of the best tracks Jarre has produced. Listening to it the first time felt a bit like witnessing the return of the Prodigal Son. Part VIII is the obligatory single in the vein of Oxygene part IV: it’s not terrible, but I’ve never been entirely convinced by it.

The rest of the album doesn’t have the same vitality, but isn’t bad by any means, and Oxygene 7 - 13 must overall be considered a genuine return to form. And yet, well, when you get down to it musical sequels are by definition creatively redundant, a bit self-indulgent, and maybe even kind of lazy. Also, Jarre had already produced an Oxygene sequel in the form of Equinoxe, so why go back there in 1997, or again in 2016, with Oxygene 3? To use nostalgia to generate sales, perhaps? Certainly worked on me!

Not embarrassing music video

No embarrassment in this video, but not much of anything else, either.

The latter years

After Oxygene 7 - 13 I stopped being actively interested in Jarre. However in the mid 2010s, needing some music to listen to while working, and having his catalogue easily accessible on Spotify (or maybe Youtube “full album” posts, I can’t remember), I gave his post 2000s works a cursory listen. I both don’t remember and didn’t think very much of what I heard. The most curious entry was the two-volume work Electronica, a series of collaborations with other electronic music luminaries. If you’re feeling charitable, such a project is an admirable piece of outreach and limelight sharing; more cynically it could be viewed as a waning talent collaborating to maintain relevancy. The truth probably lies in between.

In recent years, however, Jarre has experienced a relative renaissance, largely nostaliga-powered: Equinoxe Infinity (2018) is actually pretty listenable, and Oxygene 3 (2016), while a bit dour, isn’t embarrassing. But for me the stand out album of the past three (nearly four) decades is the 2021 album Amazonia. Orignally constructed as background music for a photographic exhibition, it’s a vivid and revelatory piece of ambient music, featuring numerous field recordings from the Amazon basin. It’s a mix of Zoolook and Waiting for Cousteau; more understated than the former, and less rigid than the latter. To my mind it’s the most successful Jarre’s been at engaging with the minimal sensibility of the last 30 years of electronica. It gives me hope that something new of interest might come out in future, though Jarre is pushing 75.

What to make of it all

Having listened to a lot of other electronic music since I was a teenager, (mostly in the period 1970 - 2000), I will say that at his best, Jarre is a genuine giant. At his worst he’s a Eurotrash producer of Cirque du Soleil background music. Now I suppose Jarre’s commitment to demotic electronica is admirably of-the-people, but that doesn’t detract from the resulting music being uniformly shallow and embarrassing. To my mind Jarre’s best work has come about when he’s kept a lid on his ego.

It’s would be an interesting exercise to compare Jarre with other electronica producers of his generation. But who exactly are his peers? When I was growing up, Vangelis seemed to be his most obvious one - as he was the only real synth music household name, in New Zealand at least. Now that I’m more familiar with the Greek master’s work, I’m not sure they’re really fellow travellers. So who else? It seems a somewhat arbitrary choice, but I’m going to pick Edgar Froese of Tangerine Dream, because they’re roughly the same age and span largely the same period. The difference in temperament between the two is amusingly stereotypical: Jarre’s Gallic flair contrasts greatly with the phlemagtically earnest German Froese. Comparing the two in terms of quality at their artistic peaks, I’d say Jarre is more musically talented, but Froese was the greater artist, if that makes sense. (To be a bit clearer, I believe Froese had a considered and enduring vision for Tangerine Dream, whereas - the ecological themes of Oxygene excepted - Jarre’s career seems to have been an endless and only occasionally fruitful search for artistic meaning.)

A less contemporaneous but more temperamentally similar composer might be the American electronica producer Moby, who has had great successes and similar lapses in taste. And like Jarre he seems to desperately want to be a star. With this comparison Jarre comes off rather better; flawed as he is, he’s never been as undignified as Moby.

Ultimately, as much as I have praised and put the boot into Jean Michel, he remains one of life’s winners. (If nothing else, in the trouser stakes he’s chalked up relationships with Charlotte Rampling, Isabelle Adjani, Anne Parillauld, and Gong Li. ‘nuff said.) So you know, French shrug.