The Cure

I first checked in with the The Cure at the relatively elderly age of 15, around the time the remix album Mixed Up came out. I was playing Talisman(!) with some friends and my friend Mike Lindley put his copy on the stereo. He was enthusiastic about it, but I don’t remember being too fussed until the 12” version of Fascination Street lumbered balefully out of the speakers. The song felt so heavy, unlike anything I’d heard before.

But I wasn’t immediately hooked. At the time, I had just become head over heels in love with classical music, and rock seemed a bit down-market to me. Even setting snobbery aside, I discovered the Cure was championed by other people in my social circle of whom I was not especially fond. It took me months to get past this pettiness; luckily I gradually succumbed.

Although The Cure makes to me now sense now as an angsty but reasonably poppy act, to a lamentably naive teenager everything of theirs sounded cosmically confronting, be it the lachrymose album Faith or the highly commercial record Head on the Door. A consequence of this is that the Cure catalogue up to 1992 has remained sufficiently vivid to me that more than 30 years later I’m writing about them.

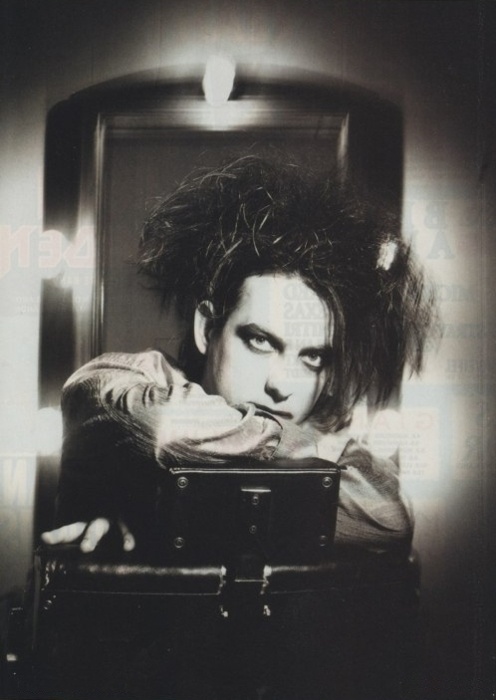

Here follows a commentary on select works by the group. Is there anything a Cure neophyte should know before I dive in? Well, the band is comprised of singer/songwriter/guitarist Robert Smith, and an evolving roster of regular, irregular, and highly irregular bandmates. In the public consciousness (at least for my age group) the band’s style is considered goth rock. Goths certainly like(d) listening to the band, although - as is universal with goth groups - Robert Smith has always denied it.

Boys Don’t Cry (1979)

This was a US compilation of the band’s first LP, Three Imaginary Boys, with adjacent singles added and filler tracks excised. We could choose to be indignant about record messing with a nascent group’s artistic vision, but in this instance the interference made for a better product.

The style is snappy if slightly weedy post-punk, and my favourite songs are Fire in Cairo and Three Imaginary Boys. As an aside, this album was on heavy rotation during the winter I turned 17. Other associations from this time: the taste of Montana “Blenheimer” Reisling casked wine (class!) and Mahler’s 6th Symphony. Good times? Well, “times”, certainly…

17 Seconds (1980)

A less chirpy and more sonically focused followup. Arguably the quintessential difficult second album in that it’s difficult to listen to. The highlight is most certainly the group’s signature song A Forest, but the other tracks are equally bleakly beautiful. Standouts for me are In Your House and M. Shout out, too to Matthieu Hartley for his understated organ work. Words I’d use to describe this album are: tight, spare, and claustrophobic.

Faith (1981)

Despite the fact it’s miserable as all get-out, I find this album quite agreeable: it’s got a sort of languorous, consumptive mood. There’s only eight songs, but each is (or at least feels like) five minutes long, so it all works out to a full album length. “There’s nothing left but faith!” wails Bob at the end. Faith’s lyrics felt intensely profound to teenage me, but now I like it more for the remote, cathedral-like production sound. What else… I love the (auto?) double-tracked bass on Other Voices, and the strumming-in-wilderness guitar on The Drowning Man. The Funeral Party is a bit cloying, and Doubt is a bit too jarringly jangly, but overall it’s a very decent, “funereal” disc. It’s worth mentioning the similarly bleak Charlotte Sometimes, a non-album single released after Faith.

Pornography (1982)

The height of the group having-a-bad-time-of-it phase. I find it hard to listen to now; not so much because of its nihilism, which is pretty insubstantial (I think Smith was in more fertile territory with his earlier interest in Camus), but because the album sounds like output of a group of men who are in a bit of a rut psychologically.

Japanese Whispers (1983)

This for me is the most interesting point of the band’s career, so I hope you’ll indulge me in a bit of explication. Between Pornograpy in 1982, and the The Top in 1984, The Cure’s release activity was limited to three singles. Things had gotten a bit complicated: bassist Simon Gallup had been ejected after the Pornography tour, and Smith hadn’t replaced him. Instead, Smith took on guitar duties for Siouxsie and the Banshees, while also running a side project, The Glove, with the Banshees’ Steve Severin. My conclusion from all this is Smith was, for a while at least, happy to put the Cure on the back burner.

I wouldn’t bother mentioning any of this if not for the fact that the songs The Cure did manage to record and release in 1983 featured a radical change in style. There’s a considerable incongruity between the first single, Let’s Go to Bed, and its predecessor, The Hanging Garden; the thundering wall (or wail) of sound of the earlier single gave way to a sly, jaunty piece of synthpop. This abrupt change must have been quite shocking for fans the group. The more energetic and Blue Monday-apeing single The Walk followed, and the playfulness reached a career zenith with the faux jazz nonsense of The Lovecats. Subsequently these singles and their B sides were compiled into a release christened Japanese Whispers.

Although it’s not a “proper” album, Japanese Whispers is my favourite Cure release. The singles are of course fun, but I absolutely adore the B sides Just One Kiss, The Upstairs Room, Lament, and The Dream. In some ways the more melancholy of these songs wouldn’t be out of place on Faith, but the use of drum machines and synths gives them a brightness that earlier songs lacked. Additionally there’s a winning “eightiesness” about the production. Thus Japanese Whispers stokes more affection in me than any other Cure record.

So what to make of all the goings on in 1983? Was the change in sound necessitated by losing a bassist and becoming studio bound? Did The Glove project make Smith more interested in try different ideas? Was Smith just tired of gloom rock and wanted to do something, anything else? I suspect it’s probably a combination of all these things. (We’ll never know, unless I bother to read a book about the band, or something…) In any event it must have been an interesting creative millieu to be bathing in.

More importantly for the band, however, the experiments of 1983 opened up new stylistic horizons for the group, which would be explored more fully over the followng three albums.

The Top (1984)

In 1984 Smith assembled a new band to record The Top, and the subsequent tour signalled that the group was fully resuscitated.

The Top shares the psychedelic mood of the Banshees’ album Hyaena from the same year (and for which Smith did guitar duties). Although it’s a “proper” album, I don’t like The Top as much as Japanese Whispers. It covers a lot of ground stylistically; most of the songs are decent enough without the album quite summing to a coherent whole. (Ok, you can say the same of Japanese Whispers, but that’s a compilation.) That said, I particularly like the agreeably weird Bananafishbones, and the extremely odd Piggy in the Mirror. I’m somewhat less fond of Give Me It and the title track.

Head on the Door (1985)

The Head on the Door marked the beginning of a period we might call “mature Cure”. The band’s personnel would be largely constant for the next four albums - the longest period of continuity the group enjoyed. Stylistically the psychedelic excesses of The Top were dialled back in favour of more radio-friendly songs. There’s still plenty of variety, and this time the songs work well together. Better still, the album was winningly commercial - arguably the most commercial album of the band’s career, although later albums would come to have greater sales. My favourite tracks are the flamenco The Blood, Six Different Ways, the utterly 1985 Push, and Screw.

Disintegration (1989)

I’m going to skip over 1987’s Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me, which has some good songs but was a bit too long for its own good. (I’m not sure I’ve ever managed to listen to it all the way through in one sitting…) One thing to note though is Kiss Me x 3 marked the end of the period started with Japanese Whispers. By late 1988 Smith was in a very different mood: about to turn 30, he feared his creative peak was now behind him. He set about trying to prove himself wrong by composing an album that expressed how he felt about things (sort of like Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, only completely self-obsessed). Happily for us Smith came to his own party, as it were, and produced a sprawling masterpiece sad longing called Disintegration. Unlike Pornography, where the emotional pain was a bit too mawkish, Disintegration features more tastefully restrained wallowing. The first half is home run after home run. My only criticism is that the songs on the second side are a bit samey, but the album does stick the landing.

Wish (1992)

I remember the excitement at my school when Wish came out (at least among us girlfriendless sensitive types): it was the first album released since we’d become fans. On mature reflection it’s a fairly ho-hum record, notable only for being Cure-gone-grunge. There’s also an irritating tweeness to it, esp on To Wish Impossible Things. The success of the radio-friendly single Friday I’m in Love was a bit discomforting for my frenemies, but it’s fine. My favourite track from the period, however, is the B side This Twilight Garden, a wistful pop song that recalls earlier glories. I’m baffled why This Twilight Garden didn’t make it onto the album, or indeed why it wasn’t released as an A side.

The Cure played a concert in my home town in middish 1992 and I almost could have gone, only my father forbade me because he feared I’d be beaten up by gang members(?!). There was no convincing him how embarrassingly off the mark that assessment was. Jeez Dad! Anyway, apparently the gig was amaazing, but in adulthood I’m not too fussed, really.

Afterwards

After Wish the Cure continued releasing, but with lengthier hiatuses. By the time Wild Mood Swings came out in 1996, I had grown up and was exploring quite different areas of music: I didn’t listen to it until maybe 15, 20 years later. It’s an interesting record with Smith returning somewhat to the whimsy of mid-80s Cure, but without the results being particularly affecting. Subsequent albums haven’t fared much better, unfortunately. All minds lose creative impetus eventually, like chewing gum losing its flavour, so let’s not dwell on it.

Summation

If my favourite album is Japanese Whispers, what do I think is The Cure’s best album? Well that’s tricky. Objectively I think I’d say it’s Disintegration, though 17 Seconds and Faith are more raw and perhaps more interesting. So take your

Robert Smith is a very singular fellow. In my Bauhaus essay I compared the group to Joy Division, perhaps unfairly, because I felt it was instructive. I could repeat the dose with The Cure with similar results, but I don’t think that highlights much of interest. A band more interesting to compare to is Depeche Mode, who were similarly popular and angsty. But although you can argue that songwriter Martin Gore is a reasonable analogue for Robert Smith, the band was more than just him. The Cure - with respect to founder member Lol Tolhurst, and long-time bassist Simon Gallup - is really just Robert Smith.

So who could we fairly compare Smith to? Who had a track record of reinventing his style and produced 15 years or so of great music? Well, Nick Cave is a decent choice, but I’d go further and also select David Bowie. Quite different artists certainly, but all similarly singular. I’d say critics would be more comfortable lauding Bowie and Cave than Smith, I think because Smith’s mawkish teenish romanticism doesn’t feel very grown up. And that haircut and lipstick is pretty credibility sapping… Well, I don’t disagree, and perhaps that’s why I prefer mid 80s Cure because during that period the angst was leavened with wiggy surrealism.